Friday, July 29, 2005

Thursday, July 28, 2005

Kaus on Roberts

Supreme Court nominee John Roberts appears to drive a Chrysler PT Cruiser. This may be the scariest thing I've heard about him.... Probe this issue thoroughly, Sen. Schumer!

—Mickey Kaus, in Slate

Friday, July 15, 2005

To the beach

Hayden Christensen plays Anakin Skywalker, who is increasingly lured toward what he calls the “dark side” and what the rest of us would call “frowning.”

—Anthony Lane in the New Yorker

I’ve yet to take in many of the summer blockbusters (with the exception of Revenge of the Sith—and here, Mr. Lane’s remark is all one needs to know), but will have plenty of time next week to see Batman Begins, Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, War of the Worlds, and Wedding Crashers, when I repair to the shore for a week off.

ff will return on the 25th. Surf’s up!

Thursday, July 14, 2005

Drawing Restraint

Matthew Barney’s Drawing Restraint opened last week at Kanazawa’s 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, including Drawing Restraint 9, a new film from 2005 (the previous components date from 1989-93); it travels to Seoul in the autumn and is scheduled to show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from 23 June through 19 September 2006.

The Drawing Restraint series examines the relationship between self-imposed resistance and creativity, a theme DR9 tracks through the construction and transformation of The Field, a vast sculpture of liquid vaseline which is poured, molded, cut, and reformed on the deck of the Nisshin Maru, a Japanese whaling vessel.

Björk and Barney, playing two of the storm-tossed ship’s passengers, fall in love during a ritual tea ceremony (from the press release, “the tearoom itself becomes the tea bowl as it slowly fills up with warm fluid”); eventually, the couple morph into cetaceans via amputation of the lower body. “This mutilation has nothing horrible about it, it's part of a transformation. When we cut into each other, the open flesh is not human flesh any more. It's white like whale flesh. Our legs drop off, we grow foetus-like tails and then we become whales and swim off towards the Antarctic.”

Free-associations from [scant] writings on the film:- the history of petroleum-based energy, and the evolution of the whale

- the Japanese whaling tradition;

- whale oil as a primary energy source;

- the diesel-fueled ship;

- a tanker truck loaded with hot petroleum jelly;

- the tanker led by oxen, horses, deer, and wild boar, flanked by hundreds of Japanese revelers;

- the ship departs for the Antarctic, and over weeks the mass of petroleum jelly cools;

- the cured surface of the jelly casting becomes a provocative reflection of the changing condition of the seas;

- whale processing methods and tools are used to create the sculpture;

- with the de-molding of the sculpture as the ship reaches the Southern Ocean; and

- a backdrop of luminous icebergs.

The soundtrack, composed by Björk, is profiled on her website.

Wednesday, July 13, 2005

Photobooth

Musee Mecanique photobooth

picture from Thanksgiving, 1978

(San Francisco, above Seal Rocks)

The Photobooth Blog is one-stop shopping for everything you need to know about the thangs, especially in an era where the old, four-to-a-strip ones are disappearing (they have a locator, and info for rentals in your area).

(Photo to the left of the teenage me, and pal Colin Camerer, during our salad days, on a visit to the Musee Mecanique, photo here.)

Labels: photography

Tuesday, July 12, 2005

The new economy and the pursuit of happiness

Does it really matter what one wears? I sometimes think my life might have been different if I had chosen the other wedding dress. I was getting married for the second time, and until the overcast morning of the ceremony I dithered between a bland écru frock appropriate to my age and station, which I wore that once and never again, and a spooky neo-Gothic masterpiece with a swagged bustle and unravelling seams in inky crêpe de laine, which I still possess: hope and experience.

The black dress—and other strange clothes in which I feel most like myself—was designed by Rei Kawakubo.

—Judith Thurman

Katie Holmes in CdG (from the newsstand

issue of W, courtesy of style.com).

Thus begins a terrific piece of fashion writing in the July 4 issue of The New Yorker: Judith Thurman’s “The Conceptualist,” [not available online, alas] a profile of Comme des Garçons founder Rei Kawakubo, (Confession: this blogger would regularly visit an insanely beautiful men’s suit—constructed from two different fabrics, one sewn atop the other—from CdG’s 2003 collection at the Chelsea hobbit-hole store, only to be stymied at first by price, and subsequently by middle-age spread. Sigh.) The essay won me over from the very beginning in its unabashed declamation that fashion does matter, at least on a personal level.

The portrait painted of Kawakubo, aged sixty-two, is an interesting one: she hails from a radically normal middle-class upbringing, and has made her mark by challenging notions that high fashion must emphasize the female form—her architectural dresses oppose the ideal of a Chanel suit, the gold standard for a Japanese woman after she has sown her wild fashion oats. Most interesting is a portrait of a company that prospers by marketing clothes in guerrilla stores—boutiques opened without fanfare in incongruous urban districts, perhaps without any other retail outlet, and closed precisely one year later; an insightful passage describes Kawakubo’s creative process, one that

[B]egins with a a vision, or perhaps just an intuition, about a key garment that Kawakubo hints at with some sort of koan. She gives the patterners a set of clues that might take the form of a scribble, a crumpled piece of paper, or an enigmatic phrase such as “inside-out pillowcase,” which they translate, as best they can, into a muslin—the three-dimensional blueprint of a garment.

The evocative back-and-forth, which sounds a little like a Ouija board that transmits and receives, describes a process that must certainly be resistant to the usual strictures of the MBA, and is remarkable for that reason alone.

Over the past few months, New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman has been writing in support of his new book, The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century. In his examination of the new economies of China and India (and its contrast with the U.S. economy), he stresses the need for our federal government to lead the way in improving our educational system, sometimes stressing our need to improve science and engineering studies, and at other times highlighting the need to train young adults in the art of learning itself. I generally agree with his globalist prescriptions. The world has cast its lot, and we are closer to the kernel of the capitalistic enterprise as never before: once one gets on the treadmill, it becomes more and more difficult to keep up, for the speed continues to increase, faster and faster. As Lady Thatcher is believed to have said, there is no [longer an] alternative.

But talkin’ about it and bein’ it—that’s two

different things. I mean, it’s real hard to be

free when you are bought and sold in the marketplace.

It now looks as though the late sixties were the golden age for having one’s cake and eating it, too: it was a time where one was able to drop out, at least for a time, and still retain one’s, er, “viability” in polite society. (Questions like “what are you going to do with that English degree?” had already begun to assert themselves in the mid-seventies, a time of economic malaise.)

I’m a big fan of Bennington College’s philosophy of education, one that they apply equally to students and to instructors: one shouldn’t eschew the mainstream—to the contrary, everyone is expected to be in the world, of the world—but they also instill a balance, so that graduates are equipped to work with the world on their own terms. There is a kind of “make ‘the man’ work for you, and not the other way ’round” ethos in play here, one that used to be more common (think Faulkner writing screenplays, or composer Charles Ives, working as an actuary for most of his life).

As the pace quickens, the forces of capitalism gradually eat away at the soul. (Friedman, tongue in cheek: if the French and German people are holding fast to their thirty-six-hour work week, then the Indians are willing to work a thirty-six-hour work day!) In the end, it takes more and more to hold onto one’s individuality, one’s happiness. But Rei Kawakubo’s work, and her story, are inspirational and hopeful.

Labels: politics

Friday, July 08, 2005

Shhhh!

Ten things from Nashville

1. The Belcourt Theatre: it’s hard to believe that this small building, a stone’s throw from Vanderbilt University in the neighborhood of Hillsboro Village, once housed the Grand Ole Opry from 1934 to 1936; the theatre has two screens and a calendar that changes frequently.

While in town, Cindy and I saw

Greg Araki’s Mysterious Skin (2005), a film about pedophilia that Todd Solondz wishes he could make, and one that departs from Araki’s ADD style of movie-making. The innovative emotional piece in MS is the victim’s love for the pedophile; plus

Lucretia Martel’s The Holy Girl (2004), an elliptical Argentinian film with a beautiful structure: it begins with a focus on location, on place—a Saltan hotel that is the setting for a medical convention and for a matrix of longing—and spirals out to the local environs and the building’s topology; at the same time, there is a wide funnel of chaotic activity surrounding preparations for the convention at the movie’s onset, narrowing towards a climax at the congress’ finale that is left perfectly unresolved. The coincident spirals—one opening, and one closing—makes for masterful cinema.

Both are recommended.

2. Hatch Show Print: the acme of American vernacular, a working letterpress print shop with great ambience and inspirational design dripping off the walls. Wondrous font for gifts and home decor.

3. Back to Cuba Café: At 4683 Trousdale Drive off of I-65 south of town, this strip-mall find served up the best Cuban food (and the best pork, the delicious dry-roasted lechón) I’ve ever had. Mmmm.

4. The Parthenon in Centennial Park: a weird but cool building with an unusual history, in a beautiful and welcoming public space (discussed at length in an earlier post).

5. Sleater-Kinney at the Cannery Ballroom: the gals are impressively tight in concert, as sharp and well-rehearsed as I have seen since, well, the Talking Heads in their early days. The venue is top-notch, an old warehouse just outside of town along the Eighth Street hipster corridor, with a beautiful sunset view of the skyline through the razor wire. (Inside: an intimate, long room with polished wooden floors and high ceilings, great sound.) And, of course, impossibly sexy drummer Janet Weiss, with shoulder-length locks flaying as she attacks her cymbals.

6. Frist Center for the Visual Arts: The Fragile Species, an exhibition of new work from local artists, the building, originally a magnificent Deco post office and smartly updated by repurposing the original customer service windows, lobby, mailboxes, and so on. (Yes, the family is that of the Majority Leader.)

Many of the artists were faculty from local colleges; I was impressed with Tom Thayer’s work [see #10, below] as well as Adrienne Outlaw’s shadow projections of warped bedsprings, Barbara Yontz’s garments made from hog intestines, and Victor Simmons’s S&H-green-stamp collages.

7. Grimey’s: kickass record store, pointing the way to Fern Jones.

8. The state capitol building: hey, no capitol dome!

9. George Jones playing cards.

10. Tom Thayer: an impressive and enigmatic presence in the Frist Center’s Fragile Species show, and easy to take him in via his semi-extensive website.

Earthworks

Tyler has posted from the Lightning Field, almost a year to the day I visited last summer. He notes, among many other observations, that

Looking at Lightning Field was like looking at a painting. When my eyes found one pole, it led me to the next one. The poles moved my eye around the landscape the way the discovery of objects, cats, and people in a Bonnard move my eye around the canvas.

and

I found the Lightning Field neither meditative nor introspective. When I looked at it, I thought about the field and the way my eyes moved around it, not about myself.

I felt a tension between the movement he describes, a restlessness that bothered me intermittently—I was constantly distracted by the regular patterns, the alignments of the gridded rods, unavoidable correspondencess for those with mathematical minds, and I didn’t care for the mania it sometimes evoked.

(Courtesy of MAN)

Yet, as we know, in the best earthworks the land does keep one grounded, so to speak; I tried to convey a bit of the power that the land carries in the west in my [admittedly abstract] essay on place and Los Angeles, a power to still one’s mind and to facilitate harmony with one’s surroundings, with oneself. Tyler remarks that

Land art is not about the hubris of the artist who places an object in the landscape in an attempt to draw the eye away from nature. It is about being modest, about being willing to have your art dwarfed by the earth.

I’d go a step further: land art is, in part, about the modesty of the viewer himself (or herself), a measure of the willingness of the audience to be dwarfed by the earth. Insofar as the Lightning Field interferes with the ability to experience this modesty, it fails where Heizer, Turrell, and Serra do not.

Finally, it is noteworthy to comment upon the social aspect of the work: the Lightning Field is experienced in a small group, numbering six or so, and for twenty-four hours. It is often the case that viewers experience the work, in part, with someone who they aren’t well-acquainted with, and this engenders a kind of social modesty. Furthermore, the act of discovering the Field [a process described in some detail in the MAN post] is mirrored in the dance of intimacy shared among the cabin-dwellers: a few days after leaving Quemado, I discovered that one of the folks who stayed with us in the cabin was a MacArthur fellow.

Labels: visual-culture

Thursday, July 07, 2005

Conference on the political economy of terrorism

Will someone kindly plow through this stuff [culled from a George Mason University School of Law conference on the political economy of terrorism] and summarize? There looks to be a lot of good material here:

- Analytical History of Terrorism

- Relevance of Rational Choice

- Religious Extremists and Terrorism

- The Importance of Culture

- Law and Economics Perspective on Terrorism

- Extremism, Suicide Terrorism and Authoritarianism

- Institutional Change

- International Political System, Supreme Values and Terrorism

- Terrorism as Theater: Analysis and Policy Implications

- Hiding in Plain Sight

- Designing Real Terrorism Futures

- Terrorism and Pork Barrel Spending

- The Political Economy ofFreedom, Democracy and Terrorism

- Terrorized Economies

[Courtesy of Marginal Revolution]

Labels: politics

Hip-hop Islam

As the authors of the forthcoming book, Tha Global Cipha: Hiphopography and the Study of Hip-Hop Cultural Practice (H. Samy Alim, Samir Meghelli and James G. Spady) argue, the hip-hop cultural movement needs to be examined with a seriousness of purpose and a methodology that considers the networked nature of Islam in order to reveal the hidden aspects of this highly misunderstood transglobal phenomenon. This is a cultural movement whose practitioners represent arguably some of the most cutting-edge conveyers of contemporary Islam. What will this new knowledge mean for Islamic scholars who teach courses on fiqh, Qur‘anic exegesis, Islamic civilisation, or Islam and modernity? Will this new knowledge transform our view about the impact of popular culture, particularly hip-hop culture, in constructing an Islam appropriate to the needs of contemporary society? Further, will imams revise their pedagogies in efforts to engage Muslim youth who are living in this postmodern hip-hop world?

The piece itself is a bit of a stretch, perhaps, but I’ve linked to it as much for the fact that it exists, that folks are publishing books that address the topic.

Nashville and wonder

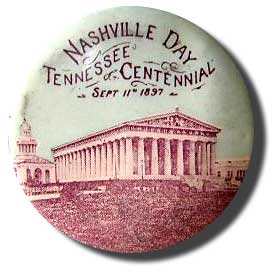

Yesterday, upon my return from Nashville, I dusted off The Parthenon, (Harvard University Press, 2003) classicist Mary Beard’s neat, readable, and illuminating volume on the West’s most famous building. I wanted to catch up on the temple’s lore, after visiting Centennial Park’s full-scale replica of the Parthenon, originally built for 1897’s Centennial Exposition in what the guidebooks like to call the “Athens of the South.”

Nashville’s Parthenon houses an exhibition about the history of the building—including glimpses into the Exposition—as well as a rather pedestrian art gallery and a replica of Athena Parthenos; the most intriguing bits were the photos and descriptions of the Centennial grounds and attractions, ripe with wonder.

As with any modern fair, the Exposition was chock full of attractions, a kind of midway denoted “Vanity Fair,” with attractions ranging from the “Streets of Cairo” (featuring a replica pyramid sponsored by Nashville’s sister city of Memphis, Tennessee; a similar attraction was featured at Chicago’s 1893 fair) to the “Cuban Village,” hawking “Mexican Dancing Girls; Cuban Dancing Girls; Spanish Dancing Girls” (photos from the 1939 World’s Fair, set in New York, show another such recreation). Other photographs show the outside of the café of Night and Morning, a live-action dramatization of Dante’s Inferno, featuring skeletons with illuminated red eyes, tables made from coffins, and chandeliers fabricated from human skulls and bones (a similar journey through heaven and hell was featured at Coney Island in 1907, according to research recorded on a UCLA website); a “cyclorama” of the battle of Gettysburg, the interior 360° mural painted over sixteen months by artists; and rides, including a giant see-saw and the chute, a car that plunged 200 feet to a shallow pool of water.

And that’s just the beginning: Algiers is reimagined in the guise of a “Moorish Palace,” with turbaned and fezzed guards ushering the visitors into a wax museum of “exotic and macabre” objects; fifteen cents purchased an admission to Thomas Edison’s “Mirage,” a theater of four life-sized motion picture images, projected via the inventor’s kinetoscope; and recreated “sham battles” offered a close-up view of the Custer’s demise at Little Bighorn.

There isn’t a hell of a lot on the web about the Exposition, so I ordered a used copy of Tenessee Centennial: Nashville 1897 (Arcadia, 1998) in their “Images of America” series: I’ve never sorted the documentation on the numerous world’s fairs of the era, but the simple fact that attractions seem to show up in different cities merits further research. Wonderous stuff.

See also: The climactic scene in Robert Altman’s Nashville—reviewed in these pages about a month ago—takes place in Centennial Park on the Parthenon’s stairs.

Tuesday, July 05, 2005

Pink

Paul Simenon of the Clash once said to me, “Pink is the only true rock ’n’ roll color.” Apparently, they painted all their equipment pink for a tour.

Labels: design, visual-culture